Jeremy O. Harris’s provocative play “Slave Play,” which premiered on Broadway in 2019, has been a focal point of intense discussion for its daring examination of race, sexuality, and power dynamics. One of the distinctive aspects of its run was the introduction of “Black Out” nights, designed to offer Black audiences an exclusive viewing experience, ostensibly to create a safe space for communal reflection and discourse. These nights were widely publicized as an effort to foster a more intimate and supportive environment for Black theatregoers, potentially unburdened by the predominantly white gaze that often dominates theatrical spaces.

The intention behind “Black Out” nights was laudable. They were conceived as evenings where only Black-identifying individuals could purchase tickets, thus aiming to center Black voices and experiences in the audience as much as on stage. The play itself, with its confrontational and often uncomfortable exploration of antebellum-themed sexual role play among contemporary interracial couples, posed challenging questions that might resonate differently within a Black audience. These special nights were intended to offer a unique atmosphere, where Black spectators could engage with the material and each other more freely.

However, the reality of these “Black Out” nights did not fully align with their advertised promise. While the concept suggested exclusivity, in practice, enforcement was lax. There were reports of non-Black individuals attending these performances, raising questions about the effectiveness and sincerity of the initiative. The notion of a completely segregated audience was more symbolic than actual, as the logistical and ethical challenges of enforcing such a policy became apparent. Theatre producers were faced with the dilemma of balancing inclusivity with the desire to create a targeted communal experience.

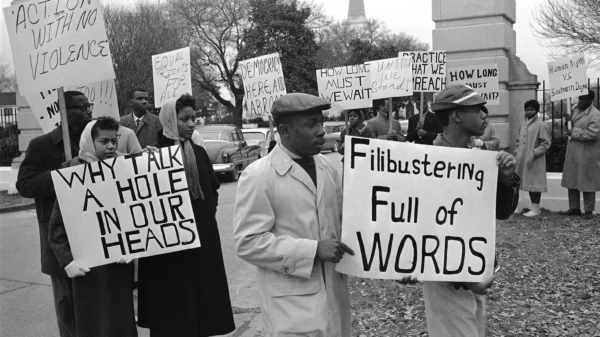

Additionally, the framing of these nights as a form of reparative justice within the arts community invited scrutiny. Critics argued that the very premise of “Black Out” nights risked reinforcing segregationist tendencies, albeit with a progressive veneer. The initiative, while progressive in its intentions, inadvertently highlighted the complexities of creating racially specific spaces within public venues. Some observers noted that while the idea was innovative, its implementation fell short of its revolutionary promise, reflecting broader societal challenges in addressing systemic inequities through performative gestures.

Furthermore, the backlash from various quarters underscored the contentious nature of the initiative. Some white audience members felt excluded, while others saw it as a necessary corrective measure in a predominantly white theatre landscape. The debates mirrored larger conversations about race relations in America, particularly around the notions of safe spaces and the need for dedicated forums for minority groups. The polarized reactions illuminated the deeply entrenched racial tensions that “Slave Play” itself sought to expose and critique.

The play’s “Black Out” nights, therefore, serve as a microcosm of the broader societal struggle to reconcile progressive ideals with practical execution. They illustrate the difficulties inherent in attempting to create inclusive yet exclusive experiences in the arts. While the nights were a bold experiment in fostering racial solidarity and offering a reprieve from the constant scrutiny of the white gaze, they ultimately highlighted the limitations and potential pitfalls of such initiatives.

In conclusion, “Slave Play’s” “Black Out” theatre nights, despite their noble intentions, became a case study in the complexities of implementing race-specific initiatives within mainstream cultural institutions. The gap between the conceptual framework and practical realities of these nights underscored the ongoing challenges in addressing racial disparities in the arts. They revealed that while the arts can be a powerful tool for social change, the path to meaningful inclusivity and equity is fraught with nuanced challenges that require more than symbolic gestures.